Pete writes about speed cameras, and the lousy statistics used in the debate about them. In a sentence, the problem is that speed cameras are installed at sites in years where there are above-average numbers of accidents; as a result, it's hardly surprising that there are fewer accidents in subsequent years. This effect is called `regression to the mean' and is a huge problem in all sorts of policy areas. (Pete is also at pains to point out that he's in favour of speed cameras, for reasons which are founded in actual thought about what they do, rather than on bad statistics.)

Many motorists are, of course, opposed to speed cameras. Typically this is because they like to drive their cars above the speed limit and don't like to be fined for doing so, though that's not normally the argument employed. Instead, these people -- 90% of whom believe that they are `above average' drivers, which is, at least, unlikely -- claim something like, ``Other drivers shouldn't speed, because that is dangerous; but I am a much safer, better driver, and therefore the law should not apply to me.''

Moving on from such dangerous nonsense, we come to a different type of sophistry, as practised by crank pressure-group The Association of British Drivers. Here the claim is that speed cameras make the roads more dangerous. Usually the argument is that cameras make drivers brake sharply, either when they notice the camera, or after they have been photographed by it. Since the cameras are placed at `dangerous' locations, this is terrible! Something must be done! Think of the children! Etc. The ABD support their theory with documents like this press release, which argues that a downward trend in road casualties slowed at the time that speed cameras were introduced. As a rule you should be suspicious of anybody who uses the word `trend' without explaining what they mean, and the ABD is no exception. What's most hilarious about this is the description of what they've done as,

A rigorous analysis of Government-published figures....

This must be some new definition of the word `rigorous' of which I was not previously aware.

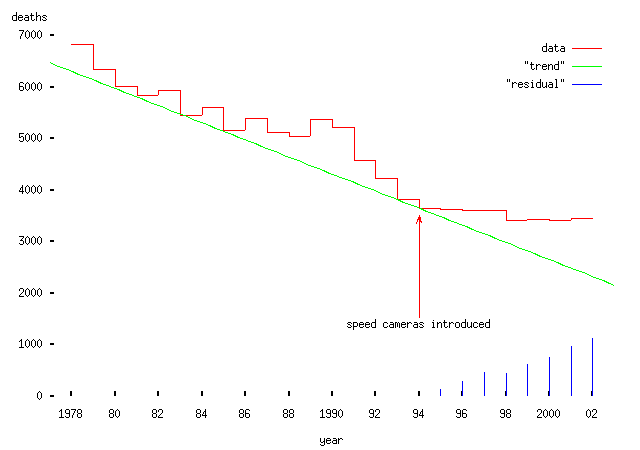

What they've done is shown in the following plot: (compare with the poorly-formatted original on the ABD site; ignore for the moment the blue curve showing vehicle usage, which is a red herring)

They've fitted a line through the number of road casualties in 1993, the year before the first cameras were introduced, and claim that this represents a `trend' in the data. Specifically their claim is that the number of fatalities in a given year should be falling by 166 each year. Then, for years after 1993 and only for those years they've plotted the difference between their `trend' line, and the actual numbers of deaths. A leap through the correlation-implies-causation window allows us to plummet to the conclusion that speed cameras `caused' these deaths.

This is, and not to put too fine a point on it, total bollocks. Among the problems with this methodology:

-

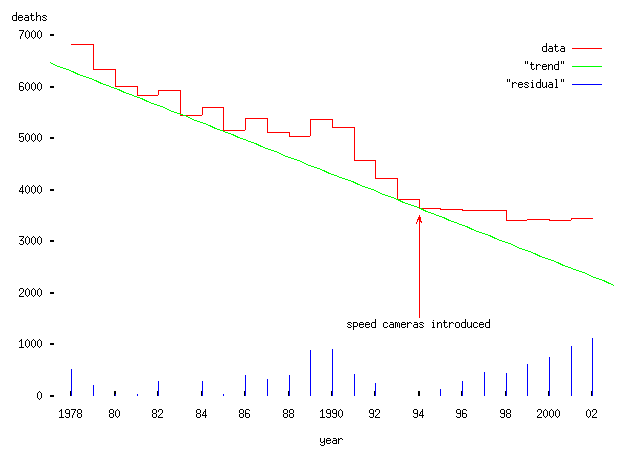

1993 was a year with a relatively low number of accident deaths. By fitting a `trend' line through the 1993 results, the ABD have ensured that all but two years appear to be above-trend (apart from 1993), as this version of the plot with the residuals for all years shows:

By selecting the year in which they fix their `trend' line to the actual data, the ABD have gone a long way towards showing the result they want.

-

Using a linear trend for road casualties is obviously wrong over some timescale. The ABD's `trend' predicts that road deaths will drop to zero some time between 2015 and 2016, and will be negative after that. Surely some mistake?

It might be more sensible to use another (non-negative) function, for instance an exponential decay, but once you've started on the selective business of statistics-by-press-release, it doesn't really matter which idiotic data `analysis' technique you use.

-

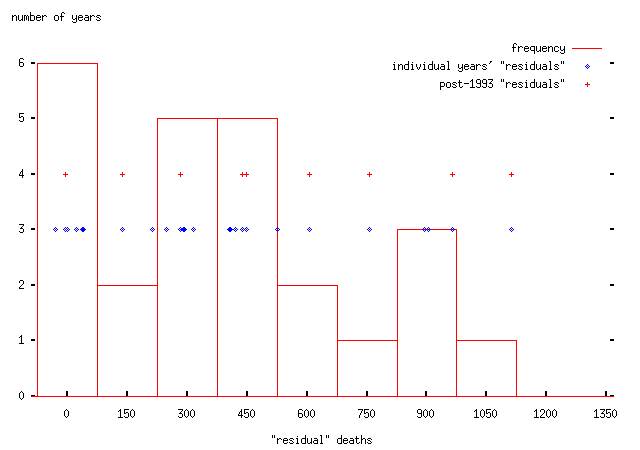

Notwithstanding the other errors, there's nothing terribly surprising about the pattern post-1993 in this analysis. In particular, it looks a lot like the post-1985 section of the graph. If we plot the frequency of the residuals themselves, we find,

Without a more formal statistical test -- it's not clear that there's enough data for this to be worth doing -- it's hard to say whether the post-1993 residuals are, in general, higher than the pre-1993 ones. Certainly there's no reason to suppose so from the above plot.

- The ABD have chosen to use data only from 1978 to the present. What happened to road deaths before 1978? I don't know, and I couldn't find the data on the National Statistics web site. I suspect that the ABD couldn't either.

Even without problems 1--4, you're still stuck with the problem that correlation does not imply causation. Even if the post-1993 `residuals' show a real effect, these data don't show any evidence that speed cameras are to blame. As Pete points out, the same period coincided with the growth in popularity of mobile phones, increasing use of the roads (which would tend to increase the number of accidents) and any number of other factors. Although the ABD wins a brownie point for mentioning `regression to the mean', the rest of their `study' in no way improves the quality of the speed cameras debate. Idiots.

So, what about the speed cameras themselves?

By coincidence, the Today Programme has been doing lots of stuff on speed cameras lately. Yesterday they interviewed -- very briefly -- Paul Garvin, the Chief Constable of Durham Police, who doesn't approve of speed cameras and has refused to install large numbers of fixed cameras in the area covered by his force. The Today interview was very short and didn't really give him a chance to explain himself, but there was a much better piece in the last Sunday Telegraph, in which Garvin was quoted as saying,

... having looked at the accident statistics in this area, we find that if you break down the 1,900 collisions we have each year only three per cent involve cars that are exceeding the speed limit. Just 60 accidents per year involve vehicles exceeding the speed limit.

Since speed cameras presumably only deter people from driving faster than the limit, this seems a pretty good reason not to employ them for casualty reduction. But contrast this article in yesterday's Torygraph, in which David Jamieson, apparently a `road safety minister', called upon Garvin to explain a 56% rise in road accidents from 2001 to 2002. As Garvin pointed out in his Today interview, County Durham was seriously affected by the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, and in 2001 there was much less traffic than in a normal year. Of course there were fewer accidents in 2001 than in 2002. It was interesting to listen to the Chief Constable explaining this on the radio, coming so close to discussing the idea of `regression to the mean' more generally, and then stepping back from the brink to allow the debate to continue along its normal slippery slope.

So, do speed cameras do any good? It's very hard to say. Accepting the premise that the point of the cameras is to make the roads safer -- implicitly there's obviously a trade-off here, since we could clearly make the roads safer by banning motor vehicles, which in darker moments of cycling 'round Cambridge sometimes seems like a good idea, but realistically would have undesirable results -- the only way to find out whether they work or not is based on actual evidence about their effects. And as Pete points out, little is forthcoming. In the interim, the best we can do is, as Paul Garvin suggests, to look at the causes of accidents. If many are caused by vehicles driving over the speed limit, then cameras might help. If not, well, it's unlikely that they will, unless the mere presence of a camera at a site makes drivers drive more carefully, or less drunkenly, or with better-maintained cars.

Nationally, the government claim that `excessive speed' is a factor in a third of fatal road accidents (repeated in numerous documents, for instance a Department of Transport paper entitled Speed cameras - Ten criticisms and why they are flawed which itself makes all of the mistakes Pete complains about). Another way of putting it comes from a frequently asked questions list for speed cameras:

Of the 3,450 people killed on Britain's roads in 2001, it is estimated that about one third resulted from collisions where speed was a contributory factor.

-- well, obviously speed is `a contributory factor'. You can't have a collision unless one party is moving, after all.

In fact, `excessive' speed is perfectly reasonably defined as speed too fast for the conditions (see, for instance, this report on an experimental `external vehicle speed control' system). Speed limits are a maximum and so don't always reflect the speed appropriate for the conditions; the problem is even more acute in the case of speed cameras. The cameras trigger at some fixed margin above the speed limit regardless of conditions and cannot be adjusted to (for instance) lower their speed theshold on foggy days. In the absence of any other figures about how many crashes involve drivers who are speeding above the limit, I think we should accept the 3% figure Garvin gives as being in the right ball-park (though obviously this must vary from area to area). Are the speed cameras worth a potential 3% reduction in accidents? That depends on how else the money could be spent, and also on the effect of the cameras on the relationship between police and policed.

The other argument for speed cameras goes, roughly, that the speed limit is the law; that it is imposed for a reason; and that it should be obeyed. Individual drivers might safely drive at higher speeds,

``But suppose everybody on our side felt that way.''

``Then I'd certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way. Wouldn't I?''

(from Catch 22 by Joseph Heller)

This is fairly reasonable, but of course we have to accept that enforcement of the law is by consent only, and we should be very careful about using measures which piss people off, lest that consent breaks down. Is it really worth scattering speed cameras around the countryside if doing so makes motorists less accepting of more serious safety measures? As a recent documentary (and a variety of A P Herbert pieces) point out, 30mph traffic -- and now paranoia about child abuse -- have left parents too concerned about the safety of their kids to let them play in the streets. This won't be an easy problem to fix. While the tabloids might replace coverage of paedophiles with some other kind of scaremongering, slowing down drivers in suburban areas is difficult.

Imposing lower speed limits in residential streets -- 10mph would be a sensible speed which would give even the dopiest of drivers time to see a child running into their path and limit the chance that they'd kill anyone even if they're too inept to stop in time -- will only work if drivers are happy to obey such limits. Pissing them off by enforcing a law they dislike elsewhere is hardly likely to achieve this effect, and it's unlikely to be practical to fill the suburbs with enforcement cameras.

There's another argument here, which is about privacy. Now, few motorists, except for the extravagantly wealthy, spend any time driving around in private, and one of the standard defences of CCTV and other automated surveillance systems is that what you do in public is... public, and it's perfectly reasonable for your public actions to be observed and any crimes discovered to be punished. (The other argument about CCTV and privacy is that `the law-abiding have nothing to fear': an argument which should be given just as much weight here as when it is used to support identity cards. Papieren, bitte?) The problem is that collecting and aggregating this data is an invasion of privacy because it enables the authorities to get much more detailed information about those it watches than (say) a police officer on a street corner with a RADAR gun (NB: not a true story) could get.

That doesn't mean that we should reject automated surveillance; the London congestion charging zone, for instance, works well and is clearly a Good Thing despite collecting data which tracks the movements of motorists. But as with speed cameras it's important to decide how much privacy to trade for how much of whatever `social good' the surveillance is supposed to get you.

Occasionally you hear talk of putting telemetry systems in cars which will limit their speed, record what happens in accidents, automatically fine people using bus lanes, and so forth. Perhaps it could even detect inept drivers, something speed cameras will never do. All of this seems broadly plausible (with any luck it good be extended to apply to my perticular bugbear, the fuckwits who stop their cars in forward stop boxes, but that might be too much to hope for, especially given that I have never heard of the Police trying to enforce the law in that case). In addition to -- hopefully -- improving road safety, such a machine could be used for navigation, help route traffic around busy areas, charge motorists depending on what roads they use rather than a blanket tax that's the same whether you drive a thousand or a hundred thousand miles in a year, and perhaps cut down on crime by making it easy to track stolen cars (depending on how many thieves learn how to disable the system and how easy it is to drive a car undetected without the black box).

But why should motorists trust the government to Do The Right Thing with a system with such potential for abuse when we have already seen them plunging onwards with speed cameras, biometric `security', and other doomed technology projects without any firm justification for their use?

While it's possible, technically, to make an in-car telemetry system which is secure and private in some sense -- that is, it will only contact Mission Control when the law is being broken or with the vehicle driver or owner's consent -- all of the objections that apply to trusting electronic voting machines apply to such a system too. In particular, drivers have to accept that what's going on inside the black box is something that they're happy with, and they have to accept that on trust since there will be no way for them to check it. (Incidentally, while electronic voting can never be made acceptably secure unless it is regarded as a simple convenience measure to back up a proper paper system, I don't think that the same is true of in-car black boxes -- as long as they are sensibly designed and the debate about them is open and honest -- because in the end we are talking about a fairly marginal invasion of privacy rather than the future of our democracy.)

While the speed cameras policy has good intentions, it has not been well-handled; and the reaction to speed cameras -- both the visceral response of drivers who like to drive too fast, and that of others who believe that the policy is flawed -- suggests that other, more useful, safety measures may not be welcomed either. Which is sad.