Here's another thing that annoys me:

Home Office figures show that violent crime has risen 14%

-- as reported by BBC radio all day, and in stories on their web site like this one. No doubt the Daily Mail had an equally fair and balanced piece on the subject. (John Band has also written about the crime figures, and about CD Wow too. Oh well. I suppose the ``'blogosphere'' is nothing if not unoriginal.)

`Home Office figures', of course, show no such thing. Total crime rates are measured by the British Crime Survey, which asks a 40,000-person sample of the whole population whether they have been victims of crime. This is like an opinion poll: by asking a representative sample of people what crime they've experienced, an accurate estimate of total crime rates in the whole country can be made.

By contrast, the figures which show a 14% increase are rates of crime reported to the police. Of course, not all crime is reported to the police, for one reason or another. The reported crime figures give a self-selecting sample of all crime, and therefore are not an accurate estimate of total crime levels. Of course, those who have an interest in suggesting that crime is rising -- the media, who like sensation, and opposition politicians, who want a stick with which to beat the government -- pick whichever figures look worse; the government prefer the British Crime Survey figures, but (for instance) the BBC report this by saying,

Ministers prefer a different set of statistics....

without explaining either (a) why they prefer them, or (b) that they are more accurate.

Another comment which has been made is that, well, whatever the statistics, the most serious violent crime, murder, has risen over the past year. (Of course, murder doesn't figure in the British Crime Survey, since none of the 40,000 people in the sample can have been murdered. But murders are typically reported, so the recorded-crime figures are likely accurate here.)

There are about 850 homicides per year in the UK (of which something like a third result in convictions for murder; others are manslaughter, infanticide, or committed by somebody who is insane or later kills themself, or whatever). But last year was unusual: because of the activities of the late Dr. Harold Shipman, as revealed by the public inquiry, 172 deaths from previous years have now been recorded as murder in 2003, although they had taken place much earlier. This is about 17% of the total, a significant percentage.

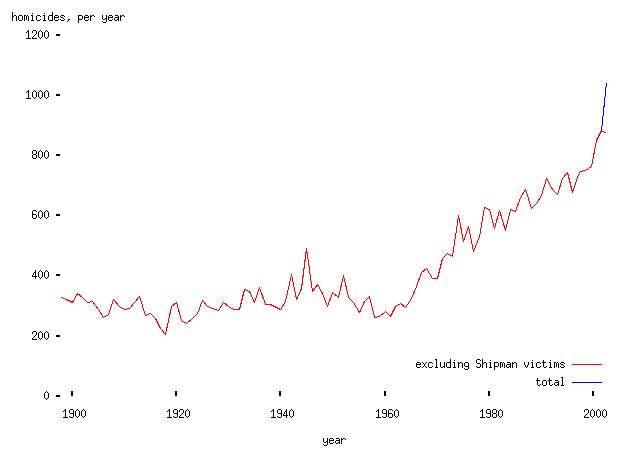

Excluding these, the homicide rate for 2002/3 was about the same as that the year before; nevertheless, homicide has become much more common since about 1960:

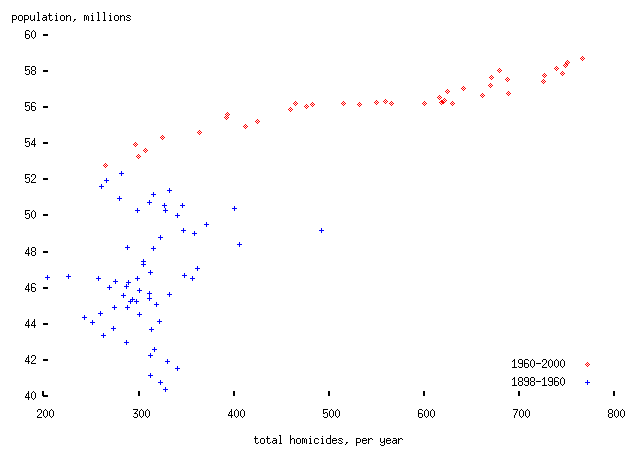

-- and this isn't just related to increasing population (more people: more killings). In fact, the total number of homicides doesn't seem to be closely related to the population:

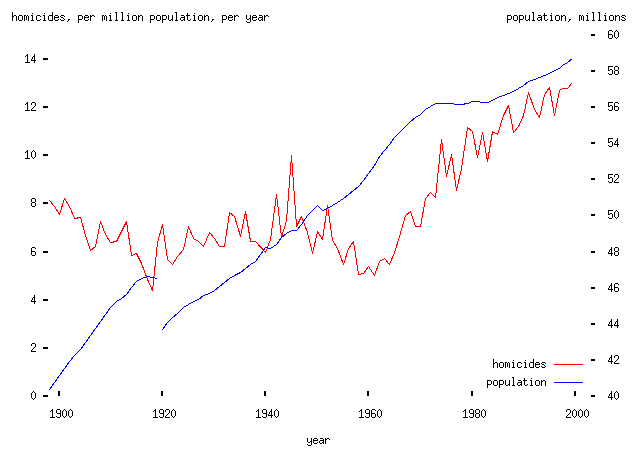

and this is reflected in the plot of homicides per million population:

(The 1919/20 discontinuity in that plot is presumably something to do with the way that population series -- which comes from the splendid What was the UK GDP Then? -- represents casualties of the First World War. It doesn't affect the plot particularly. Update: No, I was being stupid. As Anthony Wells has pointed out, the drop in 1920 is a result of the Partition of Ireland. More observant readers will recall that this took place in 1922, not 1920; however, the study from the UK GDP site explains that the population figures from 1920 onwards are given for Great Britain and Northern Ireland only. The moral? It's worth digging out this stuff to avoid looking foolish, even if you have to wade through a 98-page document to discover it.... Note also that the population series is for the whole UK, whereas the homicide figures are for England and Wales. So the per-head figures are too low, but show the correct form.)

A very interesting question is why the murder rate should have risen during this period. There are lots of theories. Gun nuts like to say that it's a result of increasing gun control; Bufton-Tuftons like to say that it's a result of the abolition of capital punishment; racists that it's to do with non-white immigration; bleeding-heart liberals that it's a result of economic inequality; prohibitionists think it's to do with drugs; puritans that it's to do with booze; trades unionists that it's to do with unemployment; and so forth. Some commentators combine several of these arguments into an incoherent whole, as with this opinion piece by Mark Steyn in (what else) the Telegraph.

The gun control argument is pretty difficult to buy into. Most homicide in England and Wales is committed with a sharp implement, and there's no evidence of large numbers of people scaring off knife-wielding attackers with guns. In any case, handguns -- the most convenient for shooting people -- have only been controlled relatively recently, and the 160,000 handguns surrendered under the 1997 Firearms Act were enough to arm only about one in 250 of the adult population, even if they had been distributed uniformly (they weren't, since many gun enthusiasts preferred to to have several...). Other data show increasing homicide rates with increasing gun ownership.

The abolition of capital punishment could have had something to do with it (hangings stopped in 1964), but it's not clear that the deterrent effect of a life sentence is much less than that of a hanging, and very few homicides are committed by repeat offenders (six out of about 500 convictions in 2000/1, of which two were homicides committed in gaol) so violent people are being removed from circulation fairly effectively even without killing them.

Unemployment has been in decline since the early 1980s, at least. Income inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) has been rising since the mid-1970s (see, for instance, the charts in this paper by Alderson and Nielsen). Daly and Wilson show (for instance, in this 1997 paper in the BMJ) that rates of homicide are significantly correlated with life expectancy (correcting for murder victims...) and income inequality among a set of data for muder rates in different parts of Chicago. (Caveat: they use stepwise regression which will overestimate the correlations of some variables.)

But in another study of US and Canadian data, the correlations observed between income inequality and homicide rates over time were much less impressive. Although the argument that income inequality -- by increasing the potential rewards of killing for the least well-off in society -- is sort-of plausible, most murders in the UK don't seem to be done for personal material gain. (An alternative is, perhaps, that the Gini coefficient is a `proxy' for something else; for instance, income inequality will differ between urban and rural areas, as will homicide rates.)

(As an aside, Daly and Wilson are also responsible for a lovely bit of research in which they showed that men's natural `discounting rate' -- which measures the present value of a future material reward -- rises when subjects are shown pictures of an attractive woman just before the experiment. They got the pictures from Am I Hot Or Not, which just goes to show that the most pointless internet site will have its day in the sun. There's no analogous discounting effect for women, or for men shown pictures of material goods -- cars, in their example. Worth a read.)

At this point it's worth reading Ted Goertzel's Econometric Modelling as Junk Science, (or see the longer version which has graphs and tables, but is in `Word' format) in which he argues that many of these types of `econometric' (meaning `regression') studies aren't much use, since they have no predictive value. In the case of homicide rates, I could obviously pick any variable which increased in the years 1960--2000 but not before then, regress the homicide rate against it, find a significant positive correlation and declare that it was the `cause' of the increased rate. But I wouldn't have learned much by doing so unless I could show that it predicted homicide rates in cases which I hadn't used to fit the model. Gortzel concludes that, despite a further quarter-century or so of work,

We are no closer to having a useful mathematical model for predicting homicide rates than we were when Ehrlich published his paper in 1975.

Ehrlich concluded that capital punishment deters homicides using a complicated regression model. Other workers used the same techniques and data to reach exactly the opposite conclusion, and a panel of experts reviewing the dispute opined that,

the emergence of a definitive behavioral study lying to rest all controversy about the behavioral effects of deterrence policies should not be expected.

-- not, perhaps, a surprise. As an alternative, Gary LaFree takes an alternative, `longitudinal' (time-domain) approach in this 1999 review, but concludes, rather unhelpfully,

The greatest impediment to longitudinal analysis is simple data availability.

He's happy that crime rates in the US fell in the 1990s, but isn't able to offer an explanation of why.

So as not to ramble on any further, I'll finish by saying that I have no idea why the homicide rate in England and Wales is rising and has been doing so since the 1960s, and I'm not certain that anyone else does either (though Peter Hitchens claims to with monotonous regularity on Start The Week, which really isn't a good thing on a Monday morning). I haven't found anything which answers the question (nor even approaches it in a very satisfactory way). If any of my half-dozen readers have any suggestions for further reading, I'd love to hear them....